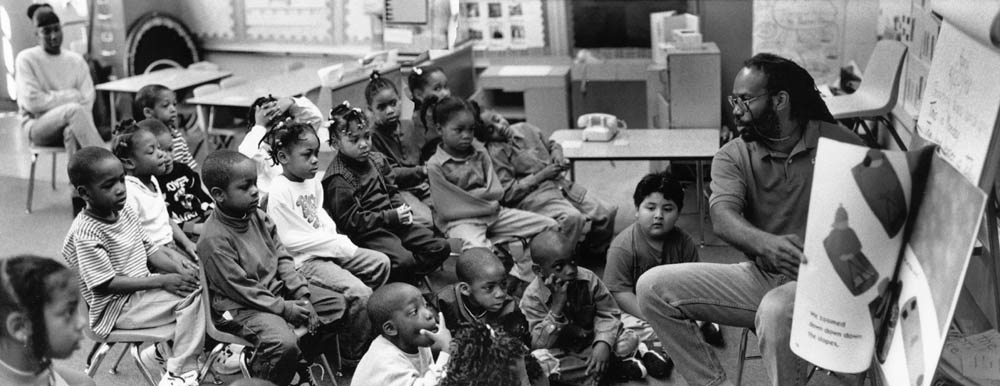

Of the 27 faculty members teaching 549 minority students at Garrison Elementary School in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington D.C., two are black males. Darryll Vann has 26 boys and girls in his kindergarten class, Hassan Abdullah 21 in his first-grade class.

In the educational and moral lives of their children, the two teachers stand, even loom, as much more than educators. They are among the few stable black males with whom the children have consistent contact. Vann and Abdullah are among the few black males regularly delivering gifts of compassion and discipline. The two men are educationally successful, both as teachers and citizens, and enter the doors at Garrison everyday knowing that, for the children, a lot—perhaps everything—is riding on the early elementary years. To the 47 boys and girls in their classes, Vann and Abdullah are the role models about whom the children can reflect, “If I become like my teacher one day, I’ll have turned out well.”

How Vann and Abdullah are using their professional and personal energies to stir the minds of some of the poorest children in one of the nation’s most administratively chaotic school systems is a story of two idealists pitting their compassion against such entrenched forces as low pay, conventional educational thinking and, often enough, disastrous home and neighborhood environments.

Garrison Elementary, named after William Lloyd Garrison, the 19th century pacifist and abolitionist, is at 12th and S Streets, NW, about a mile north of the White House and two miles west of the U.S. Capitol. Geography is about the only link to power and wealth. Ninety-six percent of the students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches. More than 90 percent live in fatherless households. Despite the social-reform successes of some local churches and civic groups, every urban blight—high unemployment, crime, street violence, drug addiction—is in the Shaw neighborhood.

One result of these combined negatives shows up annually in the Garrison reading scores. Of the 109 District elementary schools, Garrison children had the 9th lowest: 48.8 percent were reading below the basic level, with 37.7 at basic. Twelve percent were proficient and 1.5 advanced. Seventy-nine D.C. schools had a higher number of advanced readers. The Stanford 9 reading achievement tests were given in May 1997 to first through sixth graders.

As males in a traditionally female profession, Vann and Abdullah are in the conspicuous minority. In the faculties of America’s 61,165 public elementary schools, only 11 percent are men. In high schools, the number quadruples to 44 percent. Being black males, Vann and Abdulllah are minorities within a minority, and a vanishing one at that. Robert Chase, president of the National Education Association, reports that within a decade the percentage of minority public school teachers “is expected to shrink to an all-time low of five percent, while 41 percent of American students will be minorities…. Classrooms everywhere are starved for good teachers of color, particularly black and Hispanic men.” Late in 1997, the NEA awarded grants to 11 affiliates to recruit minority teachers.

My personal involvement with Garrison began in the early 1990s when, through the Center for Teaching Peace, a non-profit my wife and I began in 1985, we funded an after-school program in nonviolent conflict resolution. Many of my students at the University of Maryland and Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School served as tutors. In 1994, my son John McCarthy began Elementary Baseball, a federally funded literacy and sports program that brings in Superior Court judges, college and high school students to tutor Garrison children. More than 40 of my students have served in the program.

On one of my first visits to Garrison, I learned that the principled principal, Andrea Robinson, had been laboring mightily to recruit male teachers, especially black males. Vann and Abdullah are two rarities that resulted.

When all the politicians end their speeches on school reform, when all the editorial writers are through praising or damning vouchers, when all the task forces finish recommending one cure-all or another, it’s the lone elementary school teacher six or seven hours a day with the children who must cut through the baloney and educate. Even then, children in kindergarten have already been taught, either for good or ill, by the adults at home and by the television. Psychologists report that about 80 percent of a person’s character is shaped by the age eight.

Ebullience marks the teaching style of Darryll Vann, in his fourth year at Garrison. While speaking animatedly to his students, and with dreadlocks swinging long and loose, he moves around the room athletically. Naturally enough. He was a professional mountain biker who won prize money on the trails. At 46, and a husband for 20 years and the father of a teenager, he came to kindergarten teaching in mid-career, after doing financially well as a fashion photographer for 12 years.

One recent afternoon, while the last of his charges had found a lost lunch pail and was out the door, Vann sat near the classroom aquarium and spoke of his teaching. He is convinced that “there needs to be a positive male influence in the early grades, for the kids to see a man who nurtures. A lot of them don’t have that at home.”

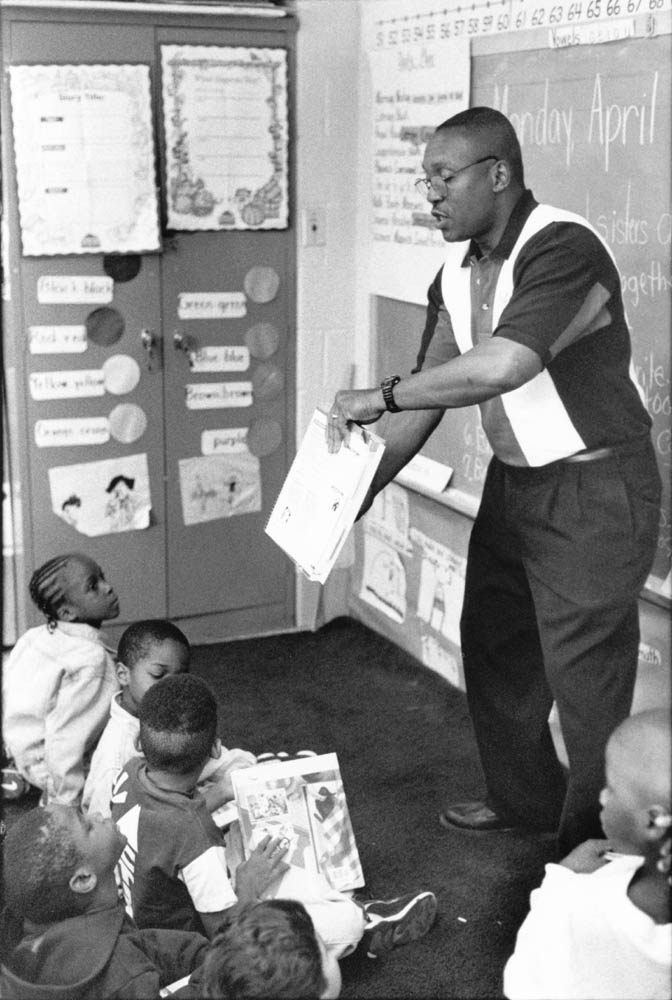

Aware that the children see him as different because he is a man, Vann teaches them by example that masculinity means being passionate about reading. Every day, large amounts of time are set aside for books: “I call parents to give them comments about their children and they tell me, ‘Mr. Vann, my son wants to get a gerbil but he’s more interested in reading a book because you do that in class. He wants me to go out and buy books.’ In these households, there might be five books total. Now parents are being forced by the children to get books, which is what I want to have happen.

“I want children to make the demand. Reading has to be interesting. If it’s a labor, no one’s going to read. I read newspapers to my children. And they see me reading the newspaper. They want to know what I’m reading. Then we sit and read it together. When they see adults reading, internally they say, ‘that must be something I need to do.’ If they’re around adults yelling at each other, they say, ‘that’s what I should be doing, so I need to yell.’”

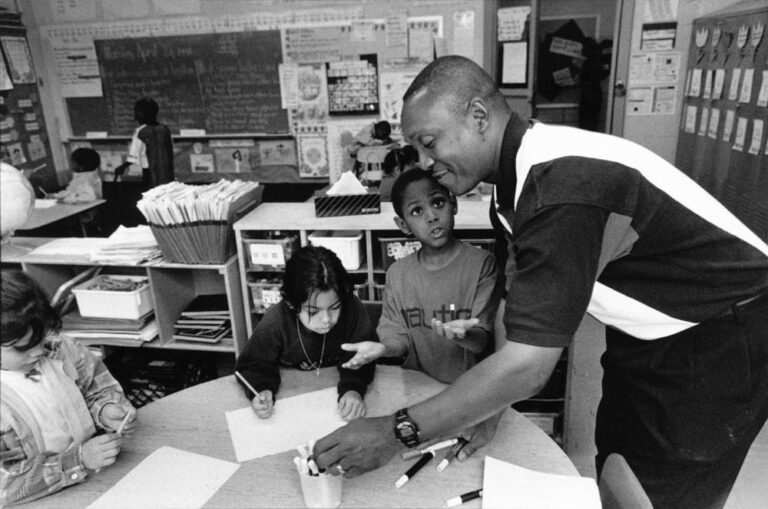

In the four years I’ve known Darryll Vann—seeing his classroom liveliness, observing him coaching for Elementary Baseball, listening to his views on education—he has been the model of a loving teacher. How loving? Vann estimates that he spends several hundred dollars a year of personal money on his students: bargain hunting for books, supplies and equipment. He loads up at garage sales in the affluent neighborhoods of Washington. His salary is well under $30,000, that sum being the bonus that several D.C. public school officials—including double dipping retired generals—received last year on top of their $100,000-plus salaries. Vann, who works part-time at a bike shop to supplement his income, is only passingly rankled by the scandal of that.

It is much the same for Hassan Abdullah. He is 48, in his fifth year at Garrison and 13th of elementary school teaching. Raised in a Baptist family in the District, he embraced the Muslim faith in 1974 after graduating from the old D.C. Teachers College. “I’m a teacher,” he said during a lunch break down the corridor from his second floor classroom, “because it’s God’s will. For a long time, I tried to avoid going into grade school teaching. I thought that it just wouldn’t look right for a man to be in a classroom with little children.”

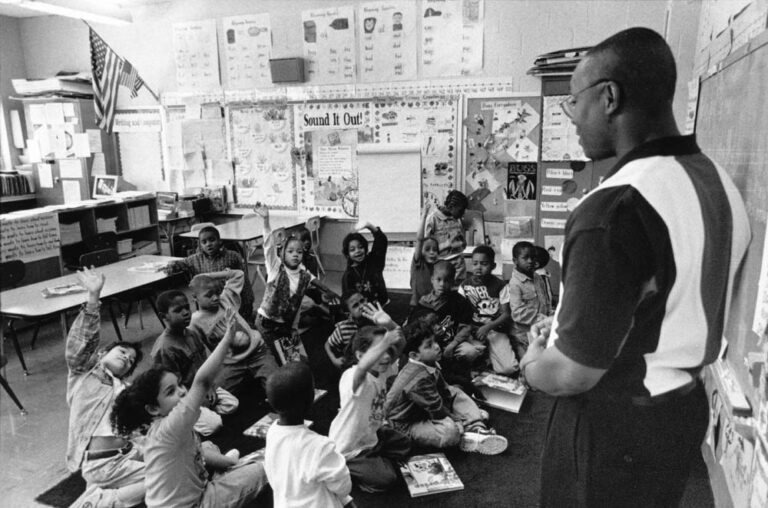

After earning a masters degree in early childhood education and working some 10 years as a consultant to state and federal school programs, Abdullah, obedient to God, was in the classroom. “From what parents have shared with me,” he says, “and from my own observations, male teachers—particularly African-American males—are making a dramatic difference in the lives of young developing children. It’s because so many come from one-parent homes, and that parent is the mother. A lot of our boys—and girls, too—have not had a nurturing relationship with a male. As a result, my students tend to listen to me. They try to adhere to the classroom rules. There’s a difference between boys and girls. If you ask girls to attend to a task, they go right away. With boys, you have to watch them all the way, or they’ll deviate. Most of the boys don’t seem to respect women, not the way I was raised.”

Abdullah—like Darryll Vann, he is athletic, having been a three letterman in high school—tells stories about his own male teachers who were positive influences. He knows it is likely he will be remembered that way, too, by many of his Garrison children. It is unimaginable that his first-graders aren’t aware that Abdullah is a special person. “I really enjoy my work,” he says. “Some days I can’t wait to get to school so I can start teaching. God has blessed me to be an elementary school teacher. I tried my best not to! I’ve had some wonderful experiences helping children to grow and begin to learn how to think.”

Few societal rewards go to elementary school teachers. The plums are reserved for college and university professors. They are well paid, they are asked by newspaper editors to review the latest books on education, often written by other professors. They are asked to write op-eds on school reform. They are given teaching assistants to handle the lowly chores of grading papers. They enjoy paid sabbaticals. Yet little of the professorial life compares with the daily arduousness of what Darryll Vann, Hassan Abdullah and most elementary school teachers go through. Under the name of “classroom teaching,” they are expected to discipline, entertain, correct, nurse, motivate, grade, call parents, fill out attendance sheets, tell kids not to run in the hall, and tell them again the next day, and the next, look for lost raincoats and rubbers, put chairs back in place, order books, hustle for more book shelves, and then go home to turn on the evening news to behold still another expert blasting “the schools” for failing.

Asked if he expects more black males to be coming into elementary schools, Abdullah states firmly, “No, I do not. It’s sad. If only black males knew how valuable they are in an elementary school, they would be flying here.”

Why aren’t they? “Coming out of a college with a bachelor’s degree to teach in the public school system doesn’t pay much. The starting salary [in the mid-$20,000s in most systems] is pathetic. You can’t blame the young men. They probably come from a household where they were the first college graduate. And now they’re asked to work hard for four or five years and still make only $24,000 a year, while other industries—even the government—are paying much more. Something has to be done.”

If the doers are the nation’s political leaders, it’s uncertain how much help is on the way. In his State of the Union speech last year, President Clinton announced his “Call to Action for American Education” based on ten principles. No. 2: “To have the best schools, we must have the best teachers…We should challenge more of our finest young people to consider teaching as a career.”

Clinton’s call included raising standards, raising teaching accountability and raising student achievement. Darryll Vann and Hassan Abdullah would have been more heartened had they also heard a call for raising salaries. They’ll keep listening.

©1998 Colman McCarthy

Colman McCarthy, a Washington freelance writer, writes for several national magazines. He is researching literacy efforts at a Washington, D.C. elementary school.