SUNFLOWER COUNTY, Miss.–The faces at the courthouse in this languid and historic central Delta county seem largely untouched by time. On Mondays, Joe Baird, John Parker, Jim Corder, Edgar Donahoe and Billy Cummins gather for supervisors’ meetings. Like generations of local officeholders before them, they are mostly farmers, men whose fortunes spring from the dusky, alluvial soil swept here thousands of years ago on the floodwaters of the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. In century-old tradition, as well, all five are white.

Across the hall is Sheriff C.O. Sessum’s office. He too is white. So are Circuit Clerk Sam Ely and Chancery Clerk Jack Harper, the county’s dominant political figure. They are not alone. The county tax assessor, the coroner, the superintendent of education, the two justice court judges, the five constables, the five election commissioners, and four of the five elected members of the school board are also white.

There is, in fact, one black elected official–school board member Lonnie Byrd-in all of county government. In the small towns of Indianola, Inverness, Ruleville and Drew, the numbers are only slightly less stark.

Blacks in Sunflower County, its seems, hold the upper hand in only one way, numerically. Three of every five residents of this once notorious county–birthplace of the white Citizens Council, home to civil rights heroine, Fannie Lou Hamer and segregationist, U.S. Sen. James O. Eastland, -are black. Their continued political domination by a white minority is another of the ironies which abound in the Delta, a land so rich with natural resources, so cursed with poverty. In Sunflower County, two decades of federal surveillance over Southern voting and an avalanche of regional change have not erased the mindset of generations. Politics is still the domain of white folk.

That Sunflower and similar counties are destined to become political relics seems unquestioned. Twenty years ago, when the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became law, there were across the South dozens of majority black counties where no black person had held political office in the 20th Century. Complete political exclusion of blacks was, with rare exception, the rule. Two decades of black activism, registration drives, lawsuits, court orders and federally-supervised redistricting plans have changed all that. With each election, it seems, the region’s Sunflower Counties move closer to extinction.

In Mississippi’s June municipal elections alone, color barriers tumbled in several major cities. Louis E. Armstrong, the director of the Mississippi Legal Services Coalition, and two other blacks became the first members of their race since Reconstruction to sit on the council in Jackson, a city where Confederate flags still wave outside some banks and hotels. Greenwood, the site of major protest efforts by blacks during the 1960s, also elected its first three black aldermen of the century. Among them was David Jordan, a local school teacher who for two decades had battled in and out of court for the political involvement of blacks. Laurel, operating like Jackson and Greenwood under a newly-imposed ward system, elected its first three black council members as well.

Still, in a dwindling number of places, time stands stationary. There, lawsuits and marches and federal registrars and the pleas of the Rev. Jesse Jackson have not undone attitudes much longer than two decades in the making. Whites remain firmly in control. The fortunes of blacks, through intimidation or apathy or black acquiescence, still rest in white hands. Across the seven southern states first covered by the Voting Rights Act (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia), there are fifteen majority-black counties, and more such towns, where the governing board is totally white. In 23 other counties, a majority of the population is black, but only one black person sits on the county commission.

Seven of those heavily-black counties where blacks have yet to win a governing board seat are in Georgia, two in Alabama, one in North Carolina, and five–including three in the Delta–in Mississippi. Sunflower County might well be the model for the rest.

“Our blacks is different,” explained Billy Cummins, a lumbering, open-faced white supervisor who farms 523 acres of Sunflower County’s incredibly fertile soil. Born poor (“I’d finished high school before we had running water in the house”), Cummins has–he believes–an innate understanding of the economic problems that face rural Mississippi blacks. That appreciation, he said, aids his continued election in a district that is 49 percent black. Familiarity with blacks has also helped white colleagues Baird Parker and Donahoe win in districts that are, respectively, 75 percent, 67 percent and 64 percent black, he said.

Such numbers are the dream of black political organizers across the nation, but in Sunflower County, they do not spell white defeat. Cummins has several explanations. One, he said, is the warm relationship he and other successful white politicians have with many blacks. Cummins appointed the first black member of the North Sunflower County Hospital board and the first–and only–black among five county road supervisors. Referring to the road supervisor, he openly boasts: “That “n…..”, Sylvester Williams, I think as much of him as of anyone, and he thinks as much of me.”

A second ingredient, Cummins said, is that many black voters simply trust the whites who have run for political office in Sunflower County more than they trust the blacks. “They’re not very well educated,” he said of the county’s black residents. “And they hadn’t seen many blacks around here that they would really trust to put their faith in.”

There are, of course, other theories, including several less complimentary to the county’s white residents. Blacks insist that economic intimidation remains alive and well in a society where black farm workers are dependent on white landowners for survival. Across the Delta, political annals are rife with stories–albeit sketchily documented–of farm owners who directed their workers to stay in the fields past sundown on election day, forcing them to miss Mississippi’s 6 p.m. poll closing. There are similar tales of catfish farms or pickling plants that happened to have pressing orders to fill on the date of a controversial election, of farm foremen who managed to increase their hires of day laborers just in time for an election, and of payoffs to poor blacks and other voting irregularities.

Even so, blacks as well as whites acknowledge that sheer numbers should give blacks a powerful voice in local politics. That volume alone has not, many say, is the product of a lingering human blight, “the plantation mentality,” a mindset grounded in illiteracy and limited education, in economic dependency and an unforgotten history of political violence. “What was done to black people over the years was a masterful job,” argues Johnnie E. Walls, Jr., a lawyer in nearby Greenville and an outspoken black activist in the Delta.

“Our fight now is a mental fight more than anything else…If you would stop and think what terror has done to black people over the years, you would understand why it’s hard to get people to flock to the polls. If they’re not afraid to vote, they just don’t know the value of it because they’ve been kept away.”

Driving down from Memphis along Route 61, the gateway to the Delta is a garish assortment of steamy fruit stands, rusting junk-yard autos, littered front yards and ramshackle filling stations. There are boarded up car washes and small, family-owned groceries, a “Power of Faith” revival tent and a group of fluorescent-yellow trailers, bursting with firecrackers and 4th of July rockets. At roadside flea markets, local hucksters, half clothed against the sweltering humidity, lounge under colorfully-striped umbrellas, and watch idly as customers sift through stacks of straw hats and second-hand shirts. Country music station WMC is crooning out “America’s Coming Back Stronger” on the car radio. And as the urban clutter gives way to wide, flat fields of cotton and soybeans, to the distant sight of white farmhouses and tarpaper-wrapped tenant shacks, there is indeed a sense that this road leads back through time to another America.

In that other day, Mississippi was the symbol of American apartheid. Its strategies to preserve separation of the races were the most ingenious; its tactics, the most ruthless; its resolve, the most complete of any southern state. In 1954, when state voters approved a constitutional amendment allowing the legislature to simply abolish public schools, rather than face integration, historian C. Vann Woodward exclaimed that the state had once again acted “in her historic role as leader of reaction in race policy, just as she had in 1875 to overthrow Reconstruction and in 1890 to disfranchise the Negro.”

To Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the Mississippi of the 1950s and 60s was “a desert state sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression.” And in 1963, when University of Mississippi professor James Silver described the magnolia state as “a closed society…as near to approximating a police state as anything we have yet seen in America,” the epithet–The Closed Society–became a focus for surging national dismay.

The history of racial violence in Mississippi ran deep as the Delta’s dark and fruitful soil. Between 1883 and 1959, by one count, some 538 black people died by lynching in the state. The episodes of the early 1960s became etched on the nation’s conscience. There were the beatings and jailing of Freedom Fighters who passed through the state in 1961, testing desegregation laws; the bloody clash of students and federal marshals as James H. Meredith tried to integrate the University of Mississippi in 1962; the death of Medgar W. Evers, field secretary for the Mississippi NAACP, shot outside his Jackson home in 1963; and in 1964, the “Mississippi Freedom Summer,” which brought to the teeming state hundreds of clergymen, housewives, professors and college students, determined to better the lives of Mississippi blacks. Three young men–two white, one black–lost their lives instead. After a six-week, nationally-watched search, their bodies were found in an earthen dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Nowhere in Mississippi was racial separation more entrenched than in the Delta, a fecund crescent stretching down the state’s northwest quarter from Memphis to Vicksburg. The region’s deep, black topsoil, the richest in the South, gave birth in the 1800s to a plantation aristocracy, based on cotton production and the sweat of black slaves. Today, thirteen of Mississippi’s 21 majority-black counties are located in the Delta, and the startling black-white gaps in education and income reflect the legacy of that bygone economic era. In Sunflower County, for instance, only one of five black residents age 25 or older had a high school education in 1980, while two of every three whites did. Median family income for whites was $18,266; for blacks, it was $7,640. With slight variations, the story in Tunica, Quitman, Tallahatchie, LeFlore, Coahoma and other Delta counties is the same.

In 1964, the year before the Voting Rights Act became law, only 28,500 blacks–six percent of those eligible–were registered to vote in Mississippi. Two years earlier, there were five Mississippi counties with black-majority populations and not a single black registered voter. Such numbers were the most appalling in the South, and the stories behind them live in the oral histories of every Delta county. In Sunflower County, for instance, older blacks still talk of Dr. Clinton Battle, a black physician who tried to register to vote in Indianola in the early 1950s. White plantation owners, they say, warned farm workers against patronizing Battle, the bank called in his loans, and he was forced to abandon his practice and leave town.

A decade later, Fannie Lou Hamer, the daughter of Sunflower County sharecroppers, was similarly punished for her attempts to register. But Hamer’s obstinance and the changing times combined for a somewhat brighter ending. In 1962, Hamer–who lived on a plantation near Ruleville–went with 17 other blacks to Indianola to register to vote. The registrar “brought a big old book out there, and he gave me the 16th section of the Constitution of Mississippi, and that was dealing with de facto laws,” Hamer later recalled. “He told me to give a reasonable interpretation…Well, I flunked out.” Returning home, Hamer also found that she and her husband had been evicted from the plantation, a result of her political foray. Undaunted, Hamer went on to stir a national audience at the 1964 Democratic presidential convention with her description of political repression in the Delta, and to become a heroine of the Southern black movement. She died in 1977.

A decade later, Fannie Lou Hamer, the daughter of Sunflower County sharecroppers, was similarly punished for her attempts to register. But Hamer’s obstinance and the changing times combined for a somewhat brighter ending. In 1962, Hamer–who lived on a plantation near Ruleville–went with 17 other blacks to Indianola to register to vote. The registrar “brought a big old book out there, and he gave me the 16th section of the Constitution of Mississippi, and that was dealing with de facto laws,” Hamer later recalled. “He told me to give a reasonable interpretation…Well, I flunked out.” Returning home, Hamer also found that she and her husband had been evicted from the plantation, a result of her political foray. Undaunted, Hamer went on to stir a national audience at the 1964 Democratic presidential convention with her description of political repression in the Delta, and to become a heroine of the Southern black movement. She died in 1977.

It was Sunflower County, as well, that gave birth in 1954 to the white Citizens Council, a sort of rotary-club version of the Ku Klux Klan, dedicated to the preservation of a segregated state. At peak in the 1950s and 60s, local councils counted prominent judges, planters and businessmen among their members. The Jackson office, by Dr. Silver’s account, had a card file detailing the racial views of almost every white person in the city, and the Council’s influence with the state legislature was legendary.

The Mississippi of 1985 is, without question, remarkably changed. In 1968, there were 29 black elected officials in a state almost 40 percent black; in 1985, there are 444, a figure surpassed only by Louisiana nationwide. There are 19 black Mississippi legislators, up from four in 1975, and a number unthinkable two decades ago. Governed by formulas that stress inclusion of both blacks and whites, the Mississippi Democratic Party has 60 white and 31 black county chairmen and co-chairmen. In 1967, there were five black lawyers in the entire state of Mississippi. Today, the first of those to graduate from the University of Mississippi–Reuben Anderson–sits on the Mississippi Supreme Court.

“Blacks and whites serve on boards together; they eat in restaurants together. It’s not fashionable to be an out and out racist,” said Bennie G. Thompson, Democratic national committeeman and a commissioner in Hinds County, outside Jackson. But Thompson, who is black, insists that the shift is more a result of changed laws than of true racial tolerance. “That’s better than where we’ve been, but it’s not where we need to get.

The gulf that still separates Mississippi blacks and whites is inescapable in the Delta. It is apparent on a hot Sunday afternoon in Tunica. At the Blue & White Restaurant, the town’s nicest, the post-church crowd is gathering to sample the day’s fare–plates piled high with fried chicken and three vegetables, pies lofty with meringue. The tables are crowded; the conversation lively. Everyone in this most prosperous restaurant in a county 73 percent black is white.

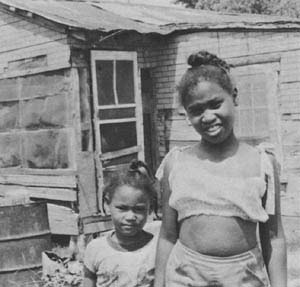

Across town, Mary Cox, four of her children and one grandchild sit in their 20 x 40 foot shanty, hammered out of ill-fitting plank boards and tarpaper. Like many of their neighbors, the family–which is black–gets its water from an outdoor tap. There is no indoor toilet, and human waste is simply tossed into a mound of rushes and scrap lumber a few yards from the house. In the winter, Mrs. Cox, a widow, stuffs rags into window cracks and nails cardboard over the door to block the cold. “I’m trying to make out ’til I can do a little better,” she says.

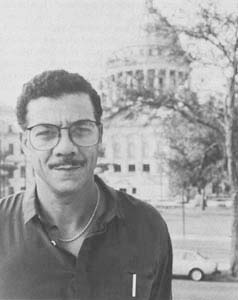

Ongoing racial division is evident, too, in Greenville to the south. There, Johnnie Walls–the black civil rights attorney–recalls a 1983 incident in which he and his wife went jogging in a white subdivision not far from their home. A friend on the police force later told him that she had been directed to check out a report involving “two blacks in a white neighborhood.” The blacks were Walls and his wife.

Just last summer, when Walls and his brother stopped to look at a house for sale in the same white neighborhood, a police officer pulled up behind them to ask if they needed help. “He assumed we had no business being there,” Walls said.

In Sunflower County, the continuing economic gap between blacks and whites is played out in numerous settings, including local bank boardrooms. The Bank of the Delta, Planters Bank and Peoples Bank of Indianola have, among them, 30 local directors. In this 62 percent black county, not a single bank director is black. “I’ve seen a lot progress in race relations, but you don’t overcome things overnight,” said James B. Randall III, president of the Indianola branch of Planters’ bank.

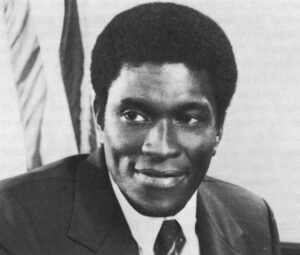

If instant proof is needed of the lingering distance between blacks and whites, one need look no further than the list of public officials in places like Sunflower County. Three contests–John Chance’s race for supervisor in 1979, and Robert G. Clark’s bids for Congress in 1982 and 1984-underscore the abiding clamp of poverty, racism and tradition on this region. Young, educated, middle-class in his values and non-controversial in style, Chance appears to be the model of what whites describe when they speak of finding a “qualified” black for whom to vote. Such credentials, however, did not propel Chance–a junior high school principal–into office in 1979. Seven out of every ten persons who are of voting age in Chance’s district are black. It was not enough. Chance lost to the longtime white incumbent, Joe B. Baird, a prominent farmer, by a vote of 733 to 474.

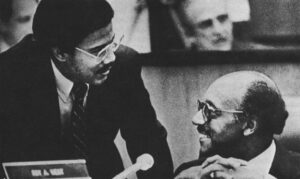

In 1982, as the Democratic nominee, Robert Clark was expected by many to become Mississippi’s first black congressman since Reconstruction. The 2nd District, carved out under the Voting Rights Act, had a small black majority in 1982, and by 1984, even the voting-age population was majority black. The district was heavily Democratic. Still, Clark–a longtime legislator who headed the House education committee–was twice stopped by Webb Franklin, a former Democratic judge turned Republican. In 1982, Franklin ran television ads picturing Clark and asking, “Do you know who my opponent is?” Racial bloc voting was rampant in the contest, and Clark was far from alone in asserting, “It would not have been a race if I had been white.” In majority-black Sunflower County, Franklin outdid Clark in 1984 by 600 votes.

The complex underpinnings of such elections cannot be separated, blacks say, from the economic dependency and lingering fear of poor blacks. Clark recalls receiving a cold shoulder from some Sunflower County blacks until he won the endorsement of several local white Democrats. “They live with those white folk; they depend on the white folk,” he said.

Chance, meanwhile, is convinced of the truth of reports that some farm hands were kept late in the fields on election day and that others were instructed by their employers to vote for Joe Baird. “There were just a number of things you couldn’t put your finger on, but you suspected a lot,” he said.

The white reaction to such assumptions is furious. Jack Harper, Sunflower County’s circuit court clerk and a man who has worked quietly for two decades to better race relations in the county, denies–as do other whites–that intimidation is at work. “The inference that black people are being held down and not permitted to vote is an outright lie against the community,” he said heatedly. “The black activists want to manage the black voting population. The black voting population doesn’t want to be managed.”

Two decades after passage of the Voting Rights Act, the seeds of change may finally be germinating in Sunflower County. Voting Rights Act challenges are expected to produce new redistricting plans for both the county and the county-seat town of Indianola by late 1985. Indianola, which will go to a ward system of elections for the first time, is almost certain to add at least one black member to a council currently composed of four whites and one black. The town is 50 percent black.

In the county at large, however, predictions for change are more cautious. The county redistricting plan, being drawn up under court order, is expected to be in place for the 1986 supervisors’ elections. Three of the five districts will have voting age populations that are majority-black. But then, three of the current five do as well. Few residents–black or white–seem confident that a handful of additional black voters in a district here, a few less there, will change age-old patterns,

“I’m not going to say Sunflower County will never have a black supervisor,” noted James Corder, chairman of the county board and a white farmer. But he is also not willing to say that a slew of court orders or a much-negotiated redistricting plan holds the magic solution for blacks. If numbers were all that mattered, he said, for Sunflower County blacks, “the opportunity’s here now.”

©1986 Margaret Edds

Margaret Edds, reporter on leave from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot/Ledger Star, is reporting on Black political power in the South.